In relating to other people, we have two main strategies. The first, empathy, amounts to simulation: how you would react in the same scenario. Yet, in the absence of analogous experiences, this can go wildly astray, with no self-correcting mechanism. By contrast, sympathy is cognitive modeling — following why someone would feel a certain way, even if they think very differently from you.

Most of us get through life by mining our past for analogies, but at extremes this breaks down. From historians trying to reconstruct forms of life of the ancient Greeks, to anthropologists meeting tribes untouched by modern society, or psychologists reaching out to patients in the depths of psychosis, sometimes these emotional ‘theories of mind’ are all we have.

I remember my surprise to hear that such a thing as ‘computational psychoanalysis’ existed. Far from the soft couch on which Freud’s patients, often neurotic Victorian housewives, laid supine, the roots of these ideas came from desperately trying to decipher straitjacketed lunatics shrieking absolute nonsense. We should expect this theory to be completely fucked, and I assure you, it is.

Much clinical research already exists on Ignacio Matte Blanco’s The Unconscious as Infinite Sets (1975). Here I want to examine its computational side, brought to light only far more recently. First, I’ll give an overview of Matte Blanco’s model of the unconscious as increasing degrees of logical symmetry; next we’ll reframe this through his later emphasis on multi-dimensional cognitive spaces; and finally, all this will be formalized in terms of ultrametric spaces in mathematics, allowing topological insights into Freudian concepts that can be implemented as machine learning algorithms for text-mining.

The Unconscious as Infinite Sets

So much of Freud has trickled into popular consciousness that it’s easy to forget just how weird his notion of the unconscious really is. Specifically, Freud notes the following defining characteristics:

- Timelessness – In recalling a repressed trauma, it’s as if you’re reliving it right now. Likewise, in dreams, people and places from various stages of life appear at once. The unconscious simply doesn’t recognize that a thing is past, and often dredges up memories we thought were lost.

- Absence of negation and contradiction – Freud famously imagines the unconscious as Rome with its various historical stages superposed atop one another, such as a church being in the same place as an ancient temple, with all these contradictory entities existing at once.

- Condensation – In dreams, numerous associations and lines of thought can be expressed in a single symbol, such as multiple people sharing some quality fused into a composite figure.

- Displacement – Feelings linked to one thing are often associated with another, such as projecting feelings about one’s father onto another male authority figure.

- Replacement of external by internal reality – A person may have a negative feeling and project it outwards, looking for something to blame it on; alternatively, a thing might be so closely connected to a bad memory that we can no longer treat it objectively.

These come up again and again in psychoanalysis, but it’s not immediately clear how they’re related. In 1959, a Chilean analyst Ignacio Matte Blanco claimed that these can be reduced to two principles.

The principle of generalization claims that the mind classifies each thing (person, object, concept) into classes sharing some quality, which in turn belong to more general classes, and so on. This operates in both conscious and unconscious thought, and is commonsensical.

The principle of symmetry claims that the unconscious treats any relation as identical to its converse, i.e. \(xRy\!\iff\!yRx\). While conscious thought allows asymmetric relations where a part belongs to a whole, or one event occurs before another, in the unconscious the whole also belongs to the part, and any ordering relation disappears. As another example, I am my father’s son and he is my son.

This sounds crazy, but that’s the point. One of Matte Blanco’s examples is a schizophrenic woman who, after doctors took a blood sample, complained that they had taken her arm away (1975: 137).

Note how these explain the characteristics of the unconscious (1976: 215). Time is an order-relation, so it disappears. With negation, \(p\) and \(\neg p\) are generalized into a wider class, and thus get treated as symmetric. Condensation is just generalization, where classes are treated as homogeneous due to symmetry. Displacement occurs when things in a class (e.g. bosses and fathers) are, by symmetry, taken as identical. Last, replacement of external by psychical reality is just a version of displacement.

Here it’s natural to ask whether there’s any mathematical object where a part can be equal to the whole. In fact, this is a defining property of infinite sets. Take for example the natural numbers \(\mathbb{N}\) and the set of even numbers. For each natural number \(n\), there is a unique even number \(2n\) corresponding to it. We say that there exists a bijective mapping between the two sets. Counterintuitively, such a mapping implies that both infinite sets are the same size.

Matte Blanco takes this in a surprisingly practical direction when he notes how emotional life is dominated by infinite quantities. It would be emotionally untruthful for a lover to say “I’ll love you for a finite amount of time.” Likewise, if you feel like a bad person, everything you’ve ever done or will do is not good enough. We could go on and on, especially for pathological thoughts. A huge part of psychoanalysis is to ‘finitize’ these emotions, putting your flaws and limitations in perspective.

Pathology, in short, is the invasion of unconscious symmetries into thought; e.g. prejudice is to view all members of a social class as the same. For Matte Blanco there is a continuum from conscious to unconscious, marked by increasing degrees of symmetry (1988: 43-5). In conscious thought, we can apprehend individual things in their singularity (first stratum); still consciously, we see how these things are interrelated, and have feelings about them (second stratum). In the third stratum, things are placed into equivalence classes, and this is where emotions of infinite degree can arise.

In the fourth stratum we reach the ‘unconscious’ proper, where equivalence classes themselves are placed into larger classes. This is where schizophrenics live: one patient said a man was very rich; when asked why, she said “He is very tall” — here the symmetric class in question is ‘things of high degree’ (1988: 44). Another noteworthy phase shift is that intense aggression involves a high degree of asymmetry (e.g. self vs. other), so is confined to the third stratum, while the fourth embodies the unconscious characteristics of lack of negation, and identification of internal and external reality.

The deepest part of the unconscious is so symmetric as to be inaccessible to asymmetric conscious thought. Everything equals everything else, and all relations between things are contained within any one thing. Hence we actually answer the question “why is the Freudian unconscious unconscious?” rather than just taking it for granted. Beyond this, however, psychoanalytical theory hits a wall.

This differs from orthodox Freudians, for whom unconscious ‘depth’ corresponds to developmental stages (oral, anal, etc.). Yet, instinct presumes asymmetric divides such as me versus ‘thing in mouth’, so for Matte Blanco it can’t be deepest (1975: 133). Further, in Freud’s later view of the unconscious as ego vs. id, the barrier between conscious and unconscious was explained by repression, whereas Matte Blanco returns to Freud’s original conception of the (mostly) ‘unrepressed unconscious’.

Matte Blanco’s work is filled with many more clinical examples, but this gives the gist of his theory. His use of mathematics is somewhat shallow, leaving many open questions, though apparently his later (untranslated) work probes the deepest layers of the unconscious by means of large cardinals. He also reframed his ideas geometrically through the notion of multi-dimensional spaces, which is worth exploring to get a more practical feel for his theory’s implications.

The n-dimensional Psyche

Matte Blanco called his theory ‘bi-logic’, to denote the disparate logics of conscious vs. unconscious thought. In fact, he was originally experimenting with multi-valued logics, and shifted to geometry as a better way to account for the facts, and this in turn gave rise to the principle of symmetry (1959: 4). Thereafter he still held on to his geometric ideas, but in an uneasy relation to his set-theoretic views.

Here it helps to start with the math. Suppose we have a triangle made from points A, B, and C. This can also be expressed as the line CABC. Notice how representing a 2D object as a 1D line entails repetition, namely of a zero-dimensional point C. A similar thing happens if we unfold a 3D cube into a 2D cross-shape. This time, not only points but also lines get repeated. In fact, this kind of repetition occurs for any projection of an \(n\)-dimensional shape onto a lower-dimensional surface.

A strikingly similar thing happens in displacement, where the same unconscious class gets manifested in many different objects. Likewise, condensation in dreams compresses disparate ideas all within one symbol, like a cubist painting on a flat canvas. Hence, a dream is a way to represent multi-dimensional mental objects for eyes made to see in a three-dimensional world (1975: 418).

In this view, the deepest level of the unconscious is an \(\infty\)-dimensional structure, and higher strata of the unconscious are lower-dimensional projections of this, bringing multiplicities along in turn.

We can also use this to think about introjection, or internalizing an object or idea (1988: 254). We’re essentially building a mental model of that thing, which has a certain dimensionality, and thus might fit well or poorly in a given part of the unconscious. If we put a model in an isodimensional stratum, then we’re good to go. It may also happen that we put our model in a certain stratum, but later find that it’s more complex, like a childood memory that a person only appreciates when they’re mature.

In most cases our mental models are incomplete, having a lower dimension than the object itself. Matte Blanco notes that this gives a new way to interpret the concept of ‘partial object’ (1988: 255).

The psychoanalyst’s task thereby becomes a process of unfolding or translating symptomatic objects from a high-dimensional space into one that consciousness can grasp (Carvalho, 2010: 234). Sanchez-Cardenas (2011) uses this to justify pluralism: rather than an analyst holding back in fear of imposing their own meaning, any interpretation has value as material to bridge psychic voids.

Matte Blanco actually uses the term ‘topological psychology’, but is far more down-to-earth than Lacan. When I have a thought or emotion, it occupies the whole of my ego; we know it’s only a part, but at the same time it’s absurd to try to localize this to a specific part. Compared to claiming that the psyche has discrete parts (like id, ego, superego), the idea that these are projections of a more complex object is almost tame in comparison. Further, there is a ‘quantitative’ aspect, where higher-dimensional objects in the psyche are associated with more intense emotions (1988: 197).

We’ve seen two very different interpretations for the same basic model of the mind, with clear parallels such as dimensionality with degree of symmetry, but striking differences as well that can’t obviously be reconciled. Nevertheless, both approaches are based on clearly-delineated principles. Thus, Matte Blanco lets us think an unconscious that is unattached to any particular person.

Formalizing Bi-Logic

As theories go, Matte Blanco’s is quite elegant, and it’s natural to ask why he’s not more well-known. The answer, I think, is terrible writing — most of The Unconscious as Infinite Sets is absolute twaddle, filled with pedantry, self-praise, and saying the same things over and over again. He seems to be much more popular in Latin America than in the Anglophone world, though has a positive reception by clinicians because he offers interpretive rules that can be used again and again among patients.

Reading Matte Blanco, one feels that he could have gone far deeper, if he only knew more math. In this vein, several attempts have been made to upgrade bi-logic into more advanced formalisms. This section is meant to show what else is out there, but I don’t find any of these approaches compelling. The reader is free to skip to the next section, where I outline a far more exciting formalization.

Rayner (1995) outlines his collaborative project to frame bi-logic through chaos theory. Matte Blanco (1988: 242) himself posited fractional dimensions of the unconscious between 2D and 3D, which we know today as fractals. Like multidimensional mental objects, chaotic structures often repeat at different scales (1995: 156), and Rayner brings up other parallels such as transitional states (‘bifurcations’ as patients gain insight), and internal objects as strange attractors (1995: 158).

The problem is that chaos is defined by sensitivity to initial conditions, making it infeasible to model empirical states, let alone something as hard to measure as the mind. Chaos was in vogue in the ’90s, but dried up once people found they couldn’t go any deeper beyond these initial metaphors.

Iurato (2018) approaches bi-logic through tools used in physics to study symmetry-breaking, or how systems transition from a symmetric to asymmetric state. In mathematics, symmetries take the form of group-theoretic operations; for example, a square is invariant when rotated 90°, so it is rotation-symmetric. Conscious thought is dominated by order-relations (asymmetric), while unconscious thought is dominated by equivalence relations (symmetric), so Iurato claims that groupoids can help us formalize the ‘break’ as unconscious thoughts their lose symmetry and become conscious.

In fact, it’s Iurato who coined the term ‘computational psychoanalysis’, which hasn’t caught on. The dealbreaker is that his papers consist of long-winded descriptions of any formal tool he can think of, without actually using these to formalize Matte Blanco’s ideas. In short, there is no actual good-faith engagement, such as through sustained examples, but only tossing around undeveloped analogies.

In yet another approach, Tomic (2020) notes that the main ingredient of quantum logic is subspaces of a Hilbert space. Logical operators are interpreted as interactions between subspaces, such as conjunction (‘and’) as intersection, or negation as a subspace’s complement. Notably, disjunction (‘or’) is defined as the linear closure of two subspaces, or all possible linear combinations of vectors in each subspace. This has the odd corollary that \(p \lor q\) can be true even if both \(p\) and \(q\) are false.

This means that from \(x \lor y \lor z\) we can derive both \(p\) and \(\neg p\), giving the principle of symmetry. We can go on to interpret a ‘class’ as a subspace, and condensation as a linear combination of qualities, but unfortunately there’s no elegant way to express the lack of time and space in the unconscious.

Battilotti (2013, 2014) likewise uses quantum logic, but starts from Matte Blanco’s thesis that 1) all sets are infinite, and 2) all relations are symmetric. The only type of set that satisfies the latter is a singleton (a set with one element), so the key is to find a way that infinite sets can act as singletons. She does this by through the concept of ‘virtual singletons’ (\(V\)) translated into logical terms, where

\[(\forall x \in V)A(x) \equiv (\exists x \in V)A(x)\]

for any formula \(A\). Thus, the set’s single element applies to an infinite number of formulas. From there things get highly technical, but the gist is that this boutique logic has both an asymmetric mode with negation, and a symmetric mode where negation is meaningless, and with no temporal processes, interpreted as logical consequence having no direction (i.e. \(A\vdash\!B\!\iff\!B\vdash\!A\)).

From the viewpoint of building a formal basis for computational psychoanalysis, I feel that quantum logic brings in way too much extra baggage, such as spin operators. This can’t be justified unless we literally believe mental objects follow quantum rules — which is insane, and not in a productive way.

While Matte Blanco based his theory on a smattering of logic and real analysis, it’s interesting to see the wide range of tools invoked to take it to a deeper level. Still, none of these really lives up to the surreal aura evoked by the term ‘computational psychoanalysis’. What we really want is something that can be implemented on a computer, but which also plugs in to a broader philosophical edifice.

Non-Archimedean Philosophy

The roots of our next approach to computational psychoanalysis come from Lauro-Grotto (2008), originally a theoretical physicist who transitioned to cognitive neuroscience. Her research involved working with dementia patients, trying to measure loss of memory. To do this, she developed a test involving photos of famous people, which the patient would classify in terms of nationality and profession; if they didn’t recognize the person, they were asked to guess.

The right and wrong answers were used as an index of ‘metric content’, or degree of similarity relations that patients perceived. She found that dementia leads to a loss of information content (as we expect), but at the same time a rise in the metric content. That is, the mind generates clusters of concepts that are internally homogeneous, such as a superclass that makes no distinction between dogs and cats. Mathematically, this is called a transition from a metric space to an ultrametric space.

Later, Lauro-Grotto encountered Matte Blanco’s book by accident, and saw the same ultrametric structure in his two principles of the unconscious: the generalization principle implies a hierarchy of classes, while the symmetry principle means that all elements of a class are indistinguishable.

I’ve stressed Lauro-Grotto’s role because of her solid foundation in both math and psychology, which makes me trust the theory far more. She’s since moved on to study mirror neurons through the lens of bi-logic, while ‘ultrametric psychoanalysis’ has been passed on to mathematicians. It turns out that the further we get into the mathematics, the more striking the parallels become. So let’s go deeper.

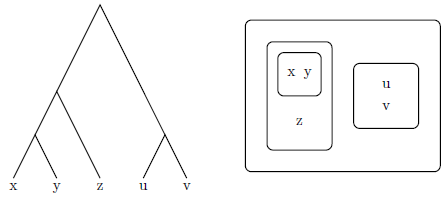

Suppose we have a triangle whose base is a line \(z\), and two more lines \(x\) and \(y\). In the worst-case scenario, \(x\) and \(y\) overlap with \(z\) to give a straight line, or triangle with zero area. Here, the lengths of \(x\) and \(y\) sum to that of \(z\), which we denote as \(d(z) = d(x) + d(y)\). The right-hand side simplifies to \(d(x + y)\), which is a lower bound for \(z\). In any other case, the combined lengths of \(x\) and \(y\) will always be greater than this. Therefore we get the triangle inequality: \(d(x + y) \leq d(x) + d(y)\).

The usual way to measure distance between points is the Euclidean metric, where if \(x=(x_1,x_2)\) and \(y=(y_1,y_2)\), then the distance between \(x\) and \(y\) is \(d_e(x,y) = \sqrt{(x_1 - y_1)^2 + (x_2 - y_2)^2}\). Other metrics are possible, such as Manhattan distance, where we can only move along a grid rather than ‘as the crow flies’ like in the Euclidean metric. Here we need to measure the horizontal and vertical distances, and add the two together, or \(d_m(x,y) = |x_1 - y_1| + |x_2 - y_2|\). A still weirder form of distance is the infinity metric, which is the maximum of the vertical and horizontal distances, or \(d_\infty(x,y) = \max\{|x_1 - y_1|, |x_2 - y_2|\}\).

A way to measure distance is a metric. Many metrics are valid, but each entails a different geometry. An example is the notion of circle, where each point has the same distance from the center [via].

Most notions of distance we are familiar with are Archimedean, where distances add up in a way we find natural, e.g. we can keep adding a number to itself until it is greater than 1. This isn’t always so. For example, number systems with infinitesimals are considered non-Archimedean.

Another non-Archimedean object is an ultrametric space, whose distances obey a stronger version of the triangle inequality, namely: \(d(x,z) \leq \max\left(d(x,y),d(y,z)\right)\). To see how ultrametric spaces defy our normal Archimedean intuitions about space, it’s easiest to illustrate their odd properties.

Consider a triangle in ultrametric space, and suppose \(d(x,y) < d(x,z)\). Then we know: \[d(y,z) \leq \max\{d(x,y), d(x,z)\} = d(x,z)\] \[d(x,z) \leq \max\{d(x,y), d(y,z)\} = d(y,z)\] and therefore, \(d(x,z) = d(y,z)\). In other words, two sides of a triangle will always have the same length, so every triangle in an ultrametric space is isosceles [via].

Another curious property is that every point of an ultrametric ball is its centre. In math, a ball is the set of points whose distance from the centre (\(a\)) is less than a given radius (\(r\)), which we can write as \(B(a,r) = \{y\:|\:d(y-a) < r\}\). Now let’s pick another point \(b\) in \(B(a,r)\) to be the new center and \(x\) in the ball with the new center, namely in \(B(b,r)\). Then \(d(y-a)<r\) and \(d(x-b)<r\) so that

\[d(x-a) = d(x - b + b\,−\,a) \leq \max\{d(x - b), d(b\,−\,a)\} < r.\]

That is, the distance of \(x\) from the old center \(a\) is still less than \(r\), so any \(x\) is in \(B(a,r)\), and hence \(B(b,r) \subseteq B(a,r)\). A similar argument lets us conclude \(B(a,r) \subseteq B(b,r)\), from which we get \(B(a,r) = B(b,r)\). So ultrametric spaces destroy our intuition that any shape has a unique centre.

One last odd property is that an ultrametric ball (or cluster) is both open and closed, or clopen, since these are not topologically exclusive: “the set is closed because objects on its boundary can be members; and it is open because the cluster extremity is defined by what is not a member relative to the external, complement set” (Murtagh, 2014a: 45). Thus a class can be defined by what it is not, which we can interpret as expressing absence of negation in the unconscious (Murtagh, 2012a: 200).

A major practical application of ultrametric spaces is phylogenetic trees, where evolutionary distance between nodes is measured by the height of their least common ancestor, which satisfies the strong triangle inequality [via]. A simple change in notation shows how this is closely related to clustering in machine learning, where clusters are ‘bags of symmetry’ subject to increasing levels of generality.

Murtagh uses this kind of clustering to raise some provocative empirical evidence for the theory. One experiment took texts from the Brothers Grimm, Jane Austen, James Joyce, air accident reports, and a database of dream reports to measure their ultrametricity values (2012b). The Brothers Grimm and accidents were lowest, and did not noticeably differ. Jane Austen had a small but distinguishably higher value. The dream reports were still higher, especially when limited to a corpus by one single dreamer; Joyce was higher than the total dream corpus, but lower than the reports by one dreamer. Conversely, the most non-ultrametric forms of time series data are those exhibiting chaos (2014c: 4).

Murtagh notes that in general, as dimensionality of data increases, distances become increasingly ultrametric — each point more and more equidistant (2020: 7). As higher-dimensional symmetries emerge, these can be exploited in algorithms to gain computational efficiency. He speculates that similar cognitive processes account for the far greater efficiency of unconscious pattern-matching over conscious reasoning (2012a: 202). The main goal in his quantitative approach to psychoanalysis is to measure degrees of condensation, ranking objects by their emotional valence (2014b: 155).

It’s also possible to build more fine-grained models using \(p\)-adic numbers, where \(p\) is some prime. As opposed to our usual notion of ‘closeness’ on the real number line, two \(p\)-adics are ‘close’ if they can both be divided by a power of \(p\); the higher the power \(p^k\), the closer they are. The \(p\)-adics form an ultrametric space, and several papers in the computational psychoanalysis literature (notably by Khrennikov) attempt to build \(p\)-adic models of the mind. Yet, the sad fact is that no-one with a deep knowledge of psychoanalysis is familiar with this way of thinking, to enrich it with empirical details.

Thinking bigger, Rejaibi et al. (2020) use deep learning to diagnose depression based on patients’ speech, and one can imagine psychoanalytic AI identifying unconscious condensations based on transcripts from analysis sessions, and perhaps even creating synthetic dreams that materialize those same complexes through virtual reality, which the analyst and patient could navigate together.

Computational psychoanalysis as a discipline can contribute to philosophy and other fields a better understanding of abstract distances between ideas. It’s a shining example of just how surreal rationality can get, and how by means of weirdness we can get a conceptual grip on deep problems.

Conclusion

Matte Blanco’s basic model of the mind consists of a nested hierarchy of classes defined by common qualities, with increasingly symmetric relations as we progress to more general superclasses, down to the deepest strata of the unconscious. From a geometric view, we can conceive the core of the unconscious as an \(\infty\)-dimensional object, whose projections onto lower-dimensional strata closer to consciousness lead to repeated volumes, manifesting as condensations in pathologies and dreams. This bizarre theory can be elegantly expressed as an ultrametric space, which has close links to machine learning, potentially opening the way for a computational approach to psychoanalysis.

By typical standards, all this is deeply whacked. Yet, I’d sooner trust a theory that 1) real psychiatrists find useful and 2) is backed up by actual math, rather than the brazen p-hacking that psychologists produce today. From the other direction, if we hope to find new applications for abstract math, we should seek out perverse kinds of reasoning that don’t conform to typical logical rules. Formalized philosophy need not imply sterile repetition — rather, expressing a concept in math means plugging it into an infinite network of entailments, extending it far deeper than its creator ever imagined.

References

- Battilotti, G. (2013). “A predicative characterization of quantum states and Matte Blanco’s Bi-logic,” in Atmanspacher, H., Haven, E., Kitto, K., Raine, D. (Eds.) (2014). Quantum Interaction. Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 184-90

- Battilotti, G. (2014). “Symmetry in sequent calculus and Matte Blanco’s bi-logic,” in Patel, S., Wang, Y., Kinsner, W., Patel, D., Fariello, G. & Zadeh, L. (Eds.). Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 13th International Conference on Cognitive Informatics & Cognitive Computing. Los Alamitos, CA: IEEE Computer Society Press, pp. 529-34

- Carvalho, R. (2010). “Matte Blanco and the multidimensional realm of the unconscious.” British Journal of Psychotherapy 26(3), pp. 324-34

- Iurato, G. (2018). Computational Psychoanalysis and Formal Bi-Logic Frameworks. Hershey, PA: IGI Global

- Lauro-Grotto, R. (2008). “The Unconscious as an Ultrametric Set.” The American Imago 64(4), pp. 52-62

- Matte Blanco, I. (1959). “Expression in Symbolic Logic of the Characteristics of the System UCS or the Logic of the System UCS.” International Journal of Psycho-Analysis 40(1), pp. 1-5

- Matte Blanco, I. (1975). The Unconscious as Infinite Sets. London: Karnac Books.

- Matte Blanco, I. (1976). “Basic logico-mathematical structures in schizophrenia,” in Kemali, D., Bartholini, G. & Richter, D. (Eds.). (1976.). Schizophrenia Today. Oxford: Pergamon Press, pp. 211-33

- Matte Blanco, I. (1988). Thinking, Feeling, and Being. New York: Routledge.

- Murtagh, F. (2012). “Ultrametric model of mind, I: Review.” p-Adic Numbers, Ultrametric Analysis and Applications 4(3), pp. 193-206

- Murtagh, F. (2012). “Ultrametric model of mind, II: Application to text content analysis.” p-Adic Numbers, Ultrametric Analysis and Applications 4(3), pp. 207-221

- Murtagh, F. (2014a). “Mathematical representations of Matte Blanco’s bi-logic, based on metric space and ultrametric or hierarchical topology.” Language and Psychoanalysis 3(2), pp. 40-63

- Murtagh, F. (2014b). “Pattern recognition in mental processes: Determining vestiges of the subconscious through ultrametric component analysis.” IEEE 13th International Conference on Cognitive Informatics & Cognitive Computing, pp. 155-61

- Murtagh, F. (2014c). “Pattern Recognition of Subconscious Underpinnings of Cognition using Ultrametric Topological Mapping of Thinking and Memory.” International Journal of Cognitive Informatics and Natural Intelligence 8(4), pp. 1-16

- Murtagh, F. (2020). “Hierarchy, Symmetry and Scale in Mathematics and Bi-Logic in Psychoanalysis, with Consequences.” European Review, forthcoming

- Rayner, E. (1995). Unconscious Logic: An Introduction to Matte Blanco’s Bi-Logic and Its Uses. New York: Routledge.

- Rejaibi, E., Komaty, A., Meriaudeau, F., Agrebi, S., Othmani, A. (2020). “MFCC-based Recurrent Neural Network for Automatic Clinical Depression Recognition and Assessment from Speech.” Working Paper.

- Sanchez-Cardenas, M. (2011). “Matte Blanco’s thought and epistemological pluralism in psychoanalysis.” The International Journal of Psychoanalysis 92(4), pp. 811-31

- Tomić, M. (2020). “Quantum Computational Psychoanalysis: Quantum Logic Approach to Bi-logic.” Working Paper.