When was the last time we had a new result in semiotics? It’s a rite of passage in the humanities to write papers full of ‘signifiers’ and ‘signifieds’, and later to problematize this model (Derrida, D&G), but the approach is largely set in stone. It’s a deep shame: if only semiotics had advanced on a par with linguistics, many fields such as human-computer interaction could have progressed far more.

If anyone can remedy this, Joseph Goguen (1941-2006) is the guy for the job. His remarkably prolific research includes categorical fuzzy set theory, inventing the OBJ family of programming languages (e.g. CafeOBJ, Maude), and creating the theory of ‘institutions’ as invariant properties of all logical systems. He was also a practicing Buddhist, and editor-in-chief of the Journal of Consciousness Studies.

All these come together in Goguen’s algebraic semiotics, which uses category theory to formalize the notion of sign-system, serving as a principled approach to user interface design. The rabbit-hole goes quite deep, and the main ideas are strewn throughout numerous papers. This post gives a self-contained introduction to algebraic semiotics, outlining semiotic morphisms as mappings between sign-systems, conceptual blending as condensation of morphisms, hidden algebra as formalizing dynamic creation of meaning, and polymorphic poetics as computational semiology.

Sign-Systems

The key insight of semiotics is that instead of meaning being inherent to a sign, signs acquire meaning differentially, through a system of oppositions. Naturally, we don’t want to spell these out, which for n signs implies n*(n-1)/2 oppositions. If we used sets as a framework, we would be in for a rough time, not least because our understandings are always only partial — this wouldn’t leave room for signs we don’t know about, or may not want to include (1999: 250).

Instead, an approach using algebra gives the structure we need while also allowing open systems. Goguen gives a formal definition of a sign-system that I’ll explain in detail, so the reader may want to just skim until the next section. A sign-system is made of the following ingredients (2004: 4):

- a signature that declares sorts, subsorts, and operations

- a subsignature of data sorts and data functions

- a set of axioms (e.g. equations) that act as constraints

- a level ordering on sorts, including a maximal ordering called ‘top’

- a priority ordering on constructors at the same level

First, a ‘sort’ is the type of a sign. It can be mundane, like separating text from numbers, but can also be elaborate, such as components of a multimedia display, with nested subsorts and supersorts. Sorts have a part-whole hierarchy (‘level ordering’): for example a menu bar and scroll bar may be on the same level, but at a lower level than the window of which they are parts (Harrell, 2013: 133).

Operations include constructors that build new signs from old signs as parts, and selectors that pull out parts from compound signs (2004: 4). Constructors can have parameters, such an image of a cat that takes parameters for its color, size, and location (Goguen & Harrell, 2005a: 86); each parameter of a constructor has a corresponding selector to extract its value (1999: 263). These more standard attributes of signs (e.g. colors, booleans, integers) are ‘data sorts’, and go in the subsignature.

Axioms are logical formulas made of constructors, functions and predicates, and constrain the set of possible signs (Goguen & Harrell, 2005a: 86). For example, we may want to stipulate that all windows on a screen are below a certain size, or that an integer has no leading zeros (Harrell, 2013: 132).

The first four items make an algebraic theory, which just means a declaration of symbols plus rules to restrict their use (1999: 244). This is what makes Goguen’s semiotics ‘algebraic’. Sometimes he refers to a sign-system as a ‘semiotic theory’, as opposed to a specific model (i.e. interpretation) that instantiates it. The class of models that satisfy a given theory is called its semiotic space (2003: 2).

Note that we add some extra structure through a priority ordering, which is assigned to constructors and their arguments to express the relative importance of the signs they build (2003: 2). Hence, “priorities indicate the relative significance of subsigns at a given level” (2004: 4). The level and priority ordering are the main ways that social context is integrated into a model.

In sum: “Sorts classify signs, operations construct signs, data sorts provide values for attributes of signs, and levels and priorities indicate saliency” (2001: 2).

Semiotic Morphisms

Any representation is a mapping from signified to signifier. A semiotic morphism is precisely this: a structure-preserving map from one sign-system to another. Instead of signifieds we have a source space, while instead of signifiers we have a target space. Understanding takes place as a process from target to source, while design proceeds from source to target (Goguen & Harrell, 2005a: 88).

Algebraic semiotics begins from the idea that we can evaluate and compare morphisms by how well they preserve structure. A good explanation or design is all about making it easy to translate from one system (e.g. words) to another (how to do something). The kinds of structure to be preserved from one sign-system to another are just the components mentioned before (Harrell, 2013: 147):

- Constructor-preserving – each contains all of the same elements

- Function-preserving – all operations are present in both spaces

- Axiom-preserving – both systems maintain the same rules

- Level-preserving – part-whole relationships are maintained

- Priority-preserving – relative importance of elements are the same

Hence semiotic morphisms map sorts to sorts, subsorts to subsorts, constructors to constructors, and so on, from source to target (Goguen & Harrell, 2005a: 88). The sign-systems need not be exactly the same, but should have corresponding structure. That is, morphisms translate “from the language of one sign system to the language of another, instead of just translating the concrete signs in the models” (1999: 256). Likewise, these mappings are partial, since we can’t expect to keep every single element, and our level and priority orderings help us decide which losses matter.

Since much of design involves choosing to preserve one thing or the other, Goguen identified several principles through detailed psychological and linguistic experiments (2001: 3):

- It is more important to preserve structure than content

- It is more important to preserve level than priority

- Structure and content at lower levels should be sacrificed in favor of those at higher levels

- Lower level constructors should be sacrificed in favor of higher level constructors

- It is more important to preserve high-level sorts than priorities (Goguen & Harrell, 2005a: 96)

These results are definitely non-obvious, and allow a principled approach to many design problems otherwise lacking solid guidelines. While most design can be done well without algebraic semiotics, the formalism really shines in resolving difficult decisions (2001: 4). One example of these principles in action was designing a proof assistant to be more pedagogically-friendly, which found that “early designs…were incorrect because the corresponding semiotic morphisms failed to preserve certain key constructors” (Goguen & Lin, 2001: 31). In a setting like teaching where students have vastly different intuitions, it could pay off to take a more abstract view to accommodate everybody.

Conceptual Blending

The easiest way to understand something we don’t know is by analogy with something we do know. Once there were no words for ‘computer virus’ or ‘roadkill’, so we just blended existing concepts.

One way to think about analogy is ‘conceptual spaces’, formalized as sets of elements with relations among them. A blending is then just a mapping from one conceptual space to another. Metaphoric blends are slightly more interesting, in that they are asymmetric: in saying “the sun is a king”, we don’t evoke every quality of a king (crown, taxes), only the most salient ones. The literature even identifies optimality principles to judge whether a blend is good or not (Goguen & Harrell, 2005b: 5).

This all sounds familiar. In fact, we can see that this framework is quite impoverished compared to semiotic morphisms: elements and relations are not typed, nor are there functions or axioms (ibid.).

Types, for instance, give us information like if a metaphor is a personification, or how ‘far apart’ are the elements being compared. Likewise, functions and axioms help account for structure, such as how a poetic meter blends with a rhyme scheme (Goguen & Harrell, 2004: 51). Most interesting of all, this enriched ‘structural blending’ can be elegantly formalized as pushouts in category theory.

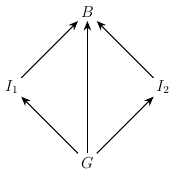

In the simplest case of conceptual blending we have a base space G (which stands for ‘generic space’) plus two input spaces 𝐼₁ and 𝐼₂. Here G,𝐼₁,𝐼₂ and their morphisms G→𝐼₁, G→𝐼₂ make up the ‘input diagram’. Likewise, a blendoid is a space B with morphisms 𝐼₁→B, 𝐼₂→B and G→B called injections. The main thing we want is symmetry, where each element of G gets mapped to the same element of B regardless of whether we choose G→𝐼₁→B, G→𝐼₂→B, or G→B, i.e. the diagram commutes.

In English: 𝐼₁ and 𝐼₂ are two things being compared, G is what they have in common, and a blend B should be consistent no matter what ‘side’ you come from. The intuition behind pushouts is that “nothing can be added to or subtracted from such an optimal blendoid without violating consistency or simplicity in some way” (2004: 13). This is mostly abstract nonsense, so let’s do an example.

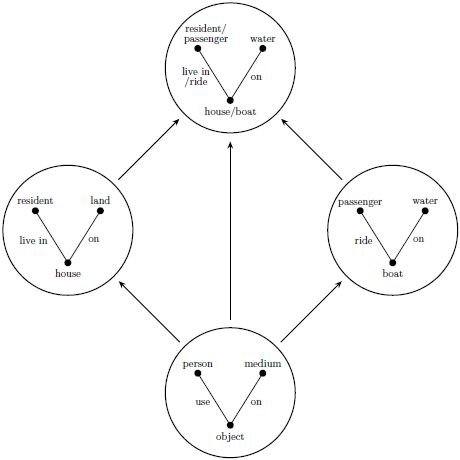

Here we see a structural blend for the term ‘houseboat’, or a boat that is used as a house. The left circle is ‘house’ (𝐼₁), the right circle is ‘boat’ (𝐼₂). The bottom circle is their common elements (G), namely that they include a person, and are on a certain medium. If you check 𝐼₁ or 𝐼₂, each gives specifics for its input. And of course, at the top we have the blend ‘houseboat’ (B). Note that for the object, person, and their relation, B combines from both inputs; yet, for the medium we only have ‘water’ — which is fine, because we only need weak equality, where each element maps to another.

Still, we can imagine other possible mappings, like ‘boathouse’ (a shelter for a boat). Goguen actually had to create a new categorical concept for this (‘3/2-pushouts’), since the output is not unique. Still, ideally we’d like to have rules so that a computer can tell which blends make sense and which don’t.

Hence, Goguen & Harrell (2005b) wrote a computer program to generate all possible blends for this example. To their surprise, there’s actually a lot — namely 2AP, where A is the number of axioms, and P is the number of primary blendoids. As far as I can tell, A=4 and P=3, giving 48 possible blendoids.

To narrow these down, they looked for optimality principles. The main challenge is that to automate these, they need to be fully formal, based on structure rather than meaning. Goguen & Harrell (2004: 52-3) ultimately arrived at degrees of commutativity (i.e. how much the arrows are ‘equal’), degree of axiom preservation (i.e. how well blends follow the rules), and amount of type casting for constants (i.e. whether a blendoid has an unnatural type). Overall, they’re satisfied that these principles match our intuition of how much a blend seems ‘boat-like’ or ‘house-like’ (Goguen & Harrell, 2005b: 16).

This example was very simple, and it turns out we can further generalize from pushouts to colimits. Colimits “capture the notion of ‘putting together’ objects to form larger objects, in a way that takes account of shared substructures” (2005: 62, fn. 14). They give an optimal blend in that “they put some components together, identifying as little as possible, with nothing left over, and with nothing essentially new added” (1999: 279). As before, we weaken these to ‘3/2-colimits’. In short, they’re a powerful tool both to combine meanings and to study the effect of context on meaning (1997: 12).

On the conceptual end, this formalism lets us think of ‘style’ as a choice of blending principles, and gives us a new language for stylistics. Notably, many artistic works make use of disoptimization principles, creating original ideas by violating our expectations (Goguen & Harrell, 2004: 56). More whimsically, Goguen curated a ‘semiotic zoo’ of bad design choices illustrating semiotic principles. (Unfortunately they’re all extremely ’90s.) While these examples are evocative, we don’t quite have a general theory — at least not until we extend our formalism to encompass sign-dynamics.

Hidden Algebra

The math of algebraic semiotics is closely related to formal verification, or proving that software is bug-free. One problem with this is that most code is written in a rush to meet deadlines, often with last-minute design changes, and just isn’t worth the trouble of verifying. Sometimes we only want to know a design works (e.g. a cryptographic protocol) and leave the code up to the user. This is called formal specification, where we prove properties of designs, as opposed to code (1997: 10).

In a static design, we want to know the different parts and what they do, which is like an algebra with elements and operations. However, in dynamic designs an operator often depends on a state that changes over time. A nice example is undo, which goes back to the state before the last command, so the computer needs to have the last state on record, to access it if needed (1999: 272).

The motivation for hidden algebra was to formalize object-oriented software (Goguen & Malcolm, 2000: 56), in which ‘objects’ have various attributes put together (e.g. a person’s name and height), visible to other objects. Each object also has a ‘hidden’ internal state that other objects can modify through methods (functions). Thus we have a division between attributes that stay the same, and states that can change. Hidden algebra is all about handling both of these at once.

While visible attributes are easy to handle with algebra, we can only find out a state by performing an experiment on it. This leads naturally to the idea that two designs are ‘equivalent’ if they behave the same in all relevant experiments (Goguen & Lin, 2000: 28). For example, practical software often doesn’t follow its specification exactly, so we may want to prove whether this makes any difference (1997: 10). Likewise, this can help if want to simplify a UI design without losing functionality.

Classical semiotics takes signs as given, but in UI design we need to think about signs that change in response to user input, or that move on their own (2004: 22). Likewise, real-world sign systems are dynamic: words change their meaning, new words are introduced, old words disappear, and even syntax changes (1999: 272). It’s common to bash structuralism for being static, but without a formalism to explicitly express changing states, ‘post-structuralist’ semiotics is no better.

This form of analysis for behaviours of hidden states is called coalgebra, a ‘dual’ to normal algebra. Even ignoring the technical details, Goguen makes a strong case that any dynamic semiotics must be coalgebraic, and hidden algebra’s strength comes precisely from combining algebra with coalgebra.

The most elaborate application so far has been Triantafyllou et al. (2014) using algebraic semiotics to measure quality of video annotations. Goguen envisioned a form of algebraic engineering for sign-systems (Goguen & Malcolm, 1999: 164), and made impressive progress in laying its foundations. Still, for this to actually catch on, it should bring not only new formalisms, but also radical new ideas.

Polymorphic Poetics

Polypoems use algebraic semiotics in a generative way to create interactive artworks. Goguen was especially interested in computational narratology, so the term isn’t limited to poetry by any means. One more poetic example is “November Qualia”, which is essentially a poem built from randomized phrases, much like Queneau’s Hundred Thousand Billion Poems. Other proposed applications include computer games that generate a plot as they are played (Goguen & Harrell, 2004: 49), computer-generated hip-hop (Goguen & Harrell, 2005b: 23), and various elaborate multimedia projects that — probably for the better — never materialized (Mamakos & Stefaneas, 2013).

Conversely, polymorphic poetics is the use of algebraic semiotics as an analytical method, describing how choices of semiotic morphisms affect the expression of a work (Harrell, 2013: 150). In UI design, it “uses morphic semiotics to help describe how meaning ‘gets into’ computing systems” (ibid., 117). Proposed applications include designing new media such as VR whose rules are not well-known, increasing usability of hardware, and supporting non-standard users such as people with disabilities (2004: 1-2). For the semiotically-inclined reader, this is probably the most compelling idea so far, but it was little developed before Goguen’s unexpected death from illness in 2016.

Some hints are there about what polymorphic poetics might have looked like if better theorized. Sadly, it’s clear that Goguen never engaged with semiotics at a graduate level. His general idea of Peirce was that he had a triadic system of signifier, signified, and an interpretant that links these two. He sees Saussure as having a more dyadic system of signifier vs. signified, but his major insight is that signs occur in sign-systems (1999: 244-5). Goguen frames his approach as similar to Peirce, whose semiotic triangle is ‘relational’, as opposed to the ‘functional’ view of Saussure (2003: 7).

An evocative illustration of the potential for algebraic semiotics is the idea that art functions through non-preservation of structure and violation of axioms (Harrell, 2004: 148). With a large enough corpus, we can imagine establishing ‘meta-rules’ of when a violation is acceptable — and these, perhaps, get violated in turn. Note, however, that algebraic semiotics is less a school of thought on its own, and more a tool to formalize diverse readings, ensuring consistency and revealing structure.

In a fascinating paper, Goguen & Borgo (2005) model free-jazz performances as nonlinear dynamical systems, where improvisation enacts the complex dynamics of musical phase space. Chiriţă & Fiadiero (2016) framed this through the lens of algebraic semiotics, creating a logic for free jazz that can be used to evaluate how it meets listeners’ expectations, find which music fragments are hardly reachable, and predict how an improvisation will evolve. This is by far the most impressive extension of algebraic semiotics thus far, and shows the deep richness that formal methods can bring.

A truly scientific theory of signs would have vast consequences for every field. For Goguen (2005), the ultimate scope of his project was a ‘unified concept theory’ using his theory of institutions to raise algebraic semiotics into a rigorous theory of knowledge representation, superseding formal concept analysis. These claims sound grandiose to the point of being crankish, but by now I hope the reader has seen that Goguen was perhaps the single person who could realistically deliver on this.

Conclusion

It’s clear that the tools are in place for a formal science of signs. Goguen’s algebraic semiotics was developed with working examples implemented in OBJ code. The main barrier has simply been that experts in semiotics have never even heard of ideas like colimits or universal algebra. Again, all of this is realizable right now — all that’s missing is someone willing to do the dirty work.

Radical ideas like ‘cognitive ergonomics’ are often tossed around for selling snake oil, but Goguen opens up the tantalizing thought that foundations for this could truly exist. We can speculate on an algebraic semiotics software added to design workflows like a debugger, optimizing user experience and potentially avoiding disastrous design flaws. We can imagine a semiotic branch of numerous sciences, such as computational biosemiotics giving us algebraic models of animal communication.

Overwhelmingly, semiotics is used as an academic acrolect to ensure that people can ‘talk the talk’, as well as dressing up insipid research to sound radical and profound. It’s time for semiotics to finally live up to its potential, as the kind of unified theory that gives post-structuralists nightmares.

References

- Chiriţă, C. & Fiadiero, J. (2016). “Free Jazz in the Land of Algebraic Improvisation.” Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Computational Creativity, pp. 322-9

- Goguen, J. (1997). “Tossing Algebraic Flowers Down the Great Divide.” University of California, San Diego.

- Goguen, J. (1999). “An Introduction to Algebraic Semiotics, with Application to User Interface Design,” in Nehaniv, C. (Ed.). (1999). Computation for Metaphors, Analogy, and Agents. Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 242-91

- Goguen, J. (2001). “Towards a Design Theory for Virtual Worlds; Algebraic semiotics, with information visualization as a case study.” Proceedings, Virtual Worlds and Simulation, Society for Modelling and Simulation, San Diego, CA, pp. 298-303

- Goguen, J. (2003). “Semiotic morphisms, representations, and blending for interface design,” in Nijholt, A., Scollo, G. & Mönnich, U. (Eds.) (2003). Proceedings of the AMAST Workshop on Algebraic Methods in Language Processing. AMAST Press, pp. 1-15

- Goguen, J. (2004). “Steps towards a Design Theory for Virtual Worlds.” Working Paper.

- Goguen, J. (2005). “What is a Concept?” in Dau, F., Mugnier, M. & Stumme, G. (Eds.). (2005). Conceptual Structures: Common Semantics for Sharing Knowledge. Proceedings of 13th International Conference on Conceptual Structures. Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 52-77

- Goguen, J. & Borgo, D. (2005). “Rivers of Consciousness: The Nonlinear Dynamics of Free Jazz,” in Fisher, L. (Ed.). Jazz Research Proceedings Yearbook, vol. 25. Kansas: IAJE Publications, pp. 46-58

- Goguen, J. & Harrell, D. (2004). “Style as a Choice of Blending Principles,” in Argamon, S., Dubnov, S. & Jupp, J. (Eds.). (2004). Style and Meaning in Language, Art Music and Design. Menlo Park: AAAI Press, pp. 49-56

- Goguen, J. & Harrell, D. (2005a). “Information visualisation and semiotic morphisms.” Studies in Multidisciplinarity 2, pp. 83-97

- Goguen, J. & Harrell, D. (2005b). “Foundations for active multimedia narrative: Semiotic spaces and structural blending.” Working Paper.

- Goguen, J. & Lin, K. (2000). “Web-based multimedia support for distributed cooperative software engineering.” Proceedings of the 2000 International Conference on Microelectronic Systems Education.

- Goguen, J. & Malcolm, G. (1999). “Signs and Representations: Semiotics for User Interface Design,” in Paton, R. & Neilson, I. (1999). Visual Representations and Interpretations. Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 163-72

- Goguen, J. & Malcolm, G. (2000). “A Hidden Agenda.” Theoretical Computer Science 245, pp. 55-101

- Harrell, D. (2013). Phantasmal Media: An Approach to Imagination, Computation, and Expression. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, ch. 4: “Polymorphic Poetics”

- Mamakos, C. & Stefaneas, P. (2013). “Polytropos Project: A Mechanism for New Media.” Symmetry: Art and Science 1-4. pp. 230-5

- Triantafyllou, N., Ksystra, K., Stefaneas, P., Kalampakas, A. (2014). “Towards Formal Represent-ation and Comparison of Video Content Using Algebraic Semiotics.” Proceedings of the 9th International Workshop on Semantic and Social Media Adaptation and Personalization, pp. 48-53