It’s a part of popular myth that the Qwerty keyboard was designed to keep old-fashioned keys from jamming, and was thus a deliberately worse design that became standard. Based on this metaphor, the object of qwernomics is “the historical, technological, and economic process of ‘lock-in’ through positive feedback”, studying ‘qwerty-worlds’ dominated by suboptimal local maxima (Land, 2016).

Of course, it’s deeply controversial whether this account of Qwerty is true, but this controversy is itself a core part of qwernomics — whether it is possible, within a path-dependent regime, to identify global criteria (such as ergonomics) that let us objectively determine if we are in a suboptimal state.

What if Qwerty isn’t the exception, but the rule? David (1985: 336) points to various other examples in economic history, and the metaphor ties in nicely with economic accounts of market failure, as well as extending to subject matter such as vestigial structures in evolutionary biology.

Nick Land’s more recent thoughts try to take the idea even further by reading the keyboard through Hjelmslev’s quadripartite semiotics, as a paradigmatic example that can take Deleuze & Guattari’s stratoanalysis from pure theory into a workable discipline. This search for nuance often amounts to a paranoiac cryptoanalysis of the keyboard’s geography, culminating in the ‘extreme qwernomic thesis’ that a future alien civilization could reconstruct all human knowledge from Qwerty alone.

My own interest in qwernomics stems from the idea of computationally simulating a sign-system (cf. egregorics). In this view, qwernomics gives a self-contained semiosis we can understand in detail. Below I’ll elaborate on this using a program to translate from Qwerty to Dvorak, revealing overlaps and invariances. Then we can examine this translation process itself through iteration, to locate even further structure. Last, I’ll explore qwernomics more deeply, and suggest further avenues to explore.

Semiotic Fixpoints

A qwernomic puzzle by @cyborg_nomade: suppose we transpose the alphabet onto the Qwerty keyboard in order: ‘q’=‘a’, ‘w’=‘b’, and so on; which keystrokes will yield English words on both the Qwerty and alphabetic keyboard? More interesting: are any words the same on both keyboards?

The latter is actually quite easy to answer — all we have to do is write the letters in a list. Let’s also throw in the Dvorak keyboard to make things interesting.

alpha = ['a'..'z']

qwerty = ['q','w','e','r','t','y','u','i','o','p',

'a','s','d','f','g','h','j','k','l',

'z','x','c','v','b','n','m']

dvorak = ['p','y','f','g','c','r','l',

'a','o','e','u','i','d','h','t','n','s',

'q','j','k','x','b','m','w','v','z']If we put all the keys in a single line, we can see just by eyeballing that in Qwerty and Dvorak, the ‘x’, ‘o’, and ‘d’ keys are in the same position. Thus, words such as ‘do’, ‘ox’, ‘odd’, ‘dodo’ and ‘doxx’ are all fixpoints, taking the nth keys in both systems. (Note that these aren’t the same physical keys.)

We can confirm this by writing a Haskell function to do exactly what we would do in eyeballing, only more thoroughly. Reading from right to left, it takes two lists (e.g. xs=alpha and ys=qwerty), then zip puts them in pairs, like ('a','q'). We want to know that the two elements are equal, which is what the lambda function does (\(x,y) -> x==y). Last, filter gives us only the pairs that satisfy that equality, and map fst gives us the first element of each such pair.

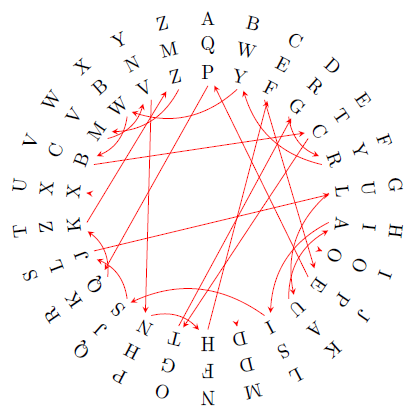

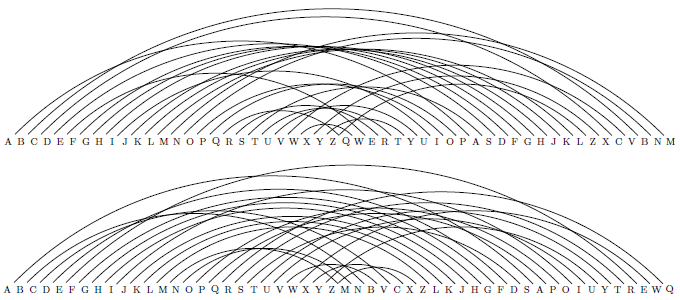

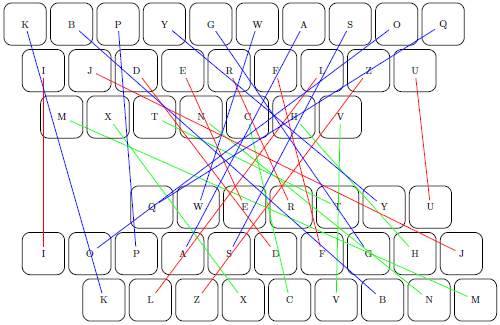

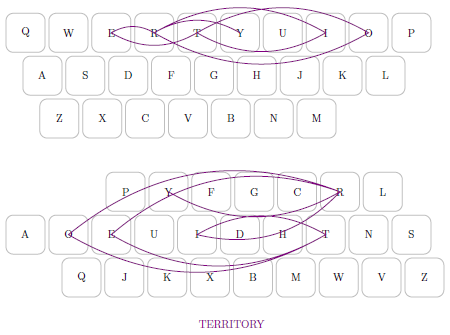

From this we find that the alphabetic and Dvorak keyboard only have ‘z’ in the same place. Last, alpha and qwerty have no pairs: no words are the same on both keyboards. We can visualize these correspondences as follows, going clockwise from 90°.

For finding ‘revolving pairs’ between alphabetic and Qwerty, @eccehetero has already done this in Java (code; results). Notably, he points out its similarity to cryptography, such as the Caesar cipher. Since alpha-to-Qwerty translation is taken care of, here I’d like to experiment with Qwerty-to-Dvorak.

To compare whole words, we’ll need a function to convert from one keyboard to another. Note that this requires functions from the Data.List and Data.Maybe libraries.

convert xs ys [] = []

convert xs ys (z:zs) = (toEnum (fromEnum z + shift) :: Char) : convert xs ys zs

where kNums = zipWith (-) (map fromEnum ys) (map fromEnum xs)

shift = kNums !! fromJust (elemIndex z xs)Our function convert takes two lists — the one we’re starting from (xs), and the one we want to convert it to (ys). It also takes a string (z:zs), where z is the head or first letter of that string. The core idea is just to convert letters to numbers (fromEnum), add a ‘shift’ factor, and then convert back to letters (toEnum). We get this shift factor by pairing up letters, converting them to numbers, and subtracting. Then for a given letter z (the nth on the keyboard) we just find the corresponding shift.

To translate key-wise from Qwerty to Dvorak, we can just use map (convert qwerty dvorak) words, where words is a list of strings. One list of 58K words is available here.

First, however, convert isn’t super-efficient, since we’re reconstructing this list of shift factors over and over again for each letter. To go through an entire dictionary, it’s better to define this list separately and take it as an argument to the function. This is actually really easy, but less general:

qwertyToDvorak = zipWith (-) (map fromEnum dvorak) (map fromEnum qwerty)

convert' xs shifts [] = []

convert' xs shifts (z:zs) = (toEnum (fromEnum z + shift) :: Char) : convert' xs shifts zs

where shift = shifts !! fromJust (elemIndex z xs)With this done, the crucial function to use is the following, which converts the words and then filters out those that aren’t in the dictionary.

After back-translating the result to Qwerty, we get this list of words, in the format (qwerty,dvorak):

[("bid","wad"),("bids","wadi"),("bob","wow"),("boo","woo"),("bop","woe"),("cad","bud"),("car","bug"),("caw","buy"),("cob","bow"),("coo","boo"),("copy","boer"),("cor","bog"),("coup","bole"),("cow","boy"),("cox","box"),("dad","dud"),("did","dad"),("do","do"),("dodo","dodo"),("dog","dot"),("doh","don"),("dopy","doer"),("dor","dog"),("dot","doc"),("ear","fug"),("fag","hut"),("far","hug"),("fig","hat"),("fir","hag"),("fob","how"),("fog","hot"),("food","hood"),("fop","hoe"),("for","hog"),("gaga","tutu"),("gig","tat"),("go","to"),("goo","too"),("ha","nu"),("hag","nut"),("hic","nab"),("ho","no"),("hob","now"),("hod","nod"),("hog","not"),("if","ah"),("irish","again"),("jap","sue"),("job","sow"),("jog","sot"),("lag","jut"),("log","jot"),("low","joy"),("moo","zoo"),("odd","odd"),("of","oh"),("oh","on"),("ox","ox"),("pig","eat"),("pro","ego"),("rag","gut"),("raw","guy"),("rid","gad"),("rocs","gobi"),("rod","god"),("roo","goo"),("soh","ion"),("tag","cut"),("tap","cue"),("tic","cab"),("tog","cot"),("too","coo"),("tow","coy"),("toy","cor"),("yap","rue"),("yogi","rota")]

This gives 76 words out of 58,110, or 0.13%. Note the prevalence of words featuring ‘o’ and ‘d’, our semiotic fixpoints from before. There’s nothing too eldritch, I’m afraid — the longest is irish/again. If anyone feels brave, there’s also a dictionary of 466K words here, to root out more obscure pairings.

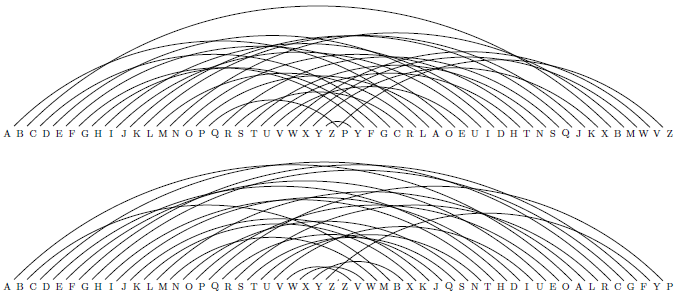

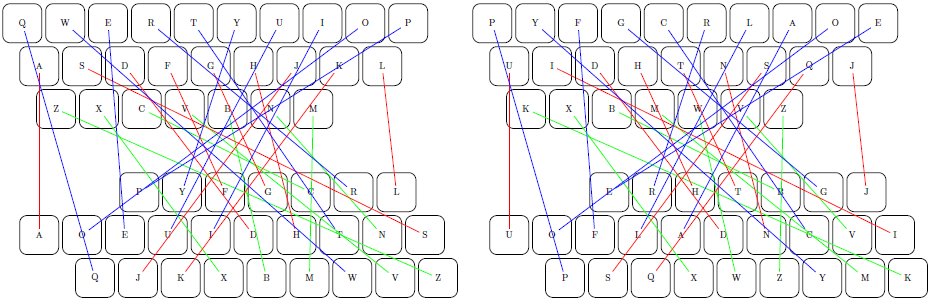

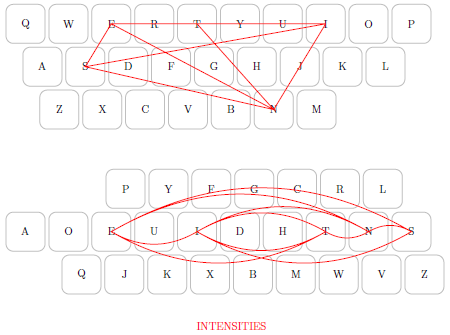

I’ve put my code in a GitHub repository, which includes both 58K-word and 466K-word dictionaries, which can be imported as a module. The code could be improved in a lot of ways — notably, it breaks if it encounters a non-alphabetic character, like an apostrophe. I’d like to come back to it once I’ve learned more about data structures and parallelism, to see if my poor laptop can handle 466K words. The repo also has TikZ code for the diagrams in this post, which may be fun to experiment with. The arcs below are inspired by a much prettier version by Amy Ireland.

Forbidden Keyboards

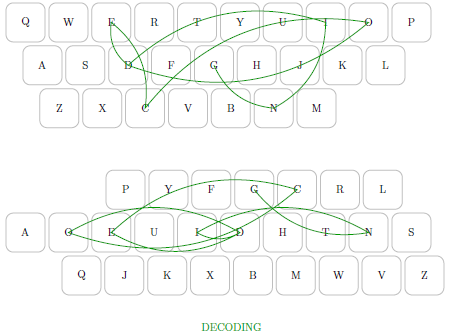

Elsewhere, @8051Enthusiast pointed out that changing from Qwerty to Dvorak is a permutation operation that can be repeated to give a Dvorak² — far more powerful than mere Dvorak¹.

All we need for this is to iterate our convert function from before. In convert qwerty dvorak qwerty, the first two arguments create a permutation from the Qwerty keyboard to a Dvorak keyboard, while the third argument (qwerty again) uses the whole Qwerty keyboard as material. Thus, to get Dvorak-squared, we can just do convert qwerty dvorak (convert qwerty dvorak qwerty).

This gives the keys "erhtbgjuofladncvipsqxwzymk", and the following diagram shows clearly that these permutations are the same.

We can write this in a more sophisticated way using the iterate function, which repeats the convert operation as many times as we want.

forbiddenDvorak n

| (n<=0) = iterate (convert dvorak qwerty) dvorak !! (abs n + 1)

| otherwise = iterate (convert qwerty dvorak) dvorak !! (n-1)Thus we can get Dvorak-cubed, up to any power n that we want. Notice that I’ve included the case where n is less than zero. This acts as an inverse function, or the reverse permutation (here from Dvorak back to Qwerty).

Perhaps the most curious aspect is that if we keep iterating our function, we’ll eventually get back to where we started. We can check this by creating a list of Dvorakn keyboards for increasingly higher powers, and seeing if any besides the first are the same as Dvorak. (The fmap (+2) is because indexing starts at zero, plus we’re excluding Dvorak¹ = Dvorak.)

This outputs Just 211, and as we can plug in and confirm, forbiddenDvorak 211 gives the Dvorak keyboard. You can likewise confirm that forbiddenDvorak 210 gives Qwerty, which of course follows.

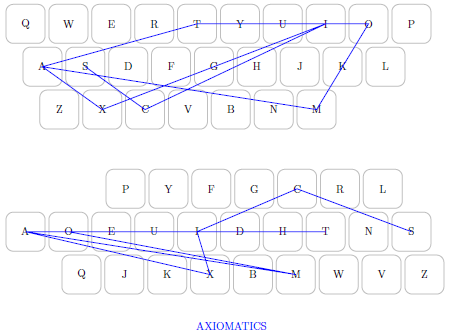

We can make an analogous function permuting alphabetical order into Qwerty:

forbiddenQwerty n

| (n<=0) = iterate (convert qwerty alpha) qwerty !! (abs n + 1)

| otherwise = iterate (convert alpha qwerty) qwerty !! (n-1)This one cycles after only 42 iterations. If the obvious association just came to mind, that’s a taste of the mix between wild coincidence and transcendental conspiracy that defines CCRU humour.

As an exercise, make a forbiddenAlpha function that converts from alphabetic to Dvorak. This one also has a cycle — it’s quite a bit larger than 250, but it’s there, and you can find it on your laptop.

I know very little about abstract algebra, but this opens up numerous interesting questions. I didn’t include punctuation for each keyboard layout, but how would these cycles change if we added it? Why does forbiddenQwerty cycle so much sooner than the others, and is there a metric to measure how ‘close’ a permutation is? Last, I can’t help but wonder if this group-theoretic structure is an artifact of our simple example, or whether it can be found in more complex sign-systems.

Qwerno-materialism

For Le (2019: 100-1), qwernomics represents how “the demands of capital accumulation led the technology of the keyboard to develop down a de-anthropomorphising path from which we could not diverge.” That is, assuming Qwerty’s inferiority, companies’ myopic refusal to train their workers in a better typographic system is “exemplary of technocapitalism’s way of locking us into a trajectory that will ultimately dehumanise us.” (Though dehumanization isn’t necessarily a bad thing!) While this may be a fair reading of Land’s original essay, in light of his 2016 lectures it’s far too glib.

Consider Nash equilibrium, where no agent can benefit by unilaterally changing their strategy. It may be, as in the Prisoner’s dilemma, that if all players changed their strategy, all could benefit, but none can on their own. Conversely, qwernomics presents a situation where any one player can unilaterally benefit from changing their strategy (e.g. a firm switching from Qwerty to Dvorak), but the societal transaction costs are so large that — across different games — they nullify this advantage.

This parallels the notion of patchwork, where normally a larger country is more efficient due to economies of scale, but now the transaction costs associated with large political institutions are so immense as to outweigh all these benefits, so on net it’s more efficient just to have a smaller state.

Choosing a keyboard is a non-ergodic process, in that we cannot freely wander through the space of possibilities toward a global optimum, where Qwerty has come out best from untrammeled market experimentation. An ergodic process tends toward a fixpoint or equilibrium, while non-ergodic systems do not, but exhibit path dependency, where states far in the past can influence states far into the future. Land perceptively notes that this division of ergodic versus non-ergodic is similar to molar (tending toward an average) versus molecular (centrifugally tending away from an average).

If Qwerty represents a ‘market solution’, Dvorak represents ‘rational planning’ from top-down. Yet, we can also imagine a centrally-planned society unwilling to escape from Qwerty lock-in, where the benefits of Dvorak are judged as not worth the cost of retraining and retooling. Thus, qwernomics is not limited to this simple opposition of interventionism versus spontaneity. In either system, transaction costs have built up over time, so that Qwerty becomes a self-installing law.

Just as Keynesian economics claims that markets get stuck in a low-employment equilibrium, which we can identify from a superior frame, we want to know by what criteria we could evaluate our path as suboptimal from a rational, Archimedean point. Ergonomics seems like the best candidate for Qwerty, but is that all a keyboard really is? The deeper notion here is that a Schelling point — an arbitrary but handy standard, like driving on the right side of the road — creates the possibility space by which we can retroactively judge it. At a certain point, the standard consumes the horizon.

As another example, Land explicitly compares Qwerty’s hegemony to that of decimal numeracy, and some mathematicians claim octal numbers are superior. Conversely, vestigial tails are evocative, but key to qwernomics is plasticity of agents’ behaviour: they’re free to use a different keyboard if they want to, but don’t — rather than having a suboptimal state biologically baked into them.

Thus, the main flaw in Le’s account is workers’ lack of agency. Moreover, instead of emphasizing suboptimality as ‘dehumanizing’, Land’s main interest is in Qwerty as a causal loop, like the bootstrap paradox in time travel. Qwerty as a code represents a radically alien form of immanence: it is authoritative because it has made itself occur.

Stratoanalysis

Land goes on to use the Qwerty keyboard as a hermeneutic device to understand Deleuze & Guattari’s “Geology of Morals”. There, stratoanalysis is introduced as a synonym for D&G’s project, alongside rhizomatics, nomadology, schizoanalysis, pragmatics, and so on. In general, stratoanalysis is very seldom invoked, but it’s actually quite rich as a framework.

The basic idea is that the world is made up of relatively autonomous codes, such as the genetic code versus body language. The system of oppositions that defines a code takes place on an independent layer or stratum. Strata interact horizontally via parastrata (codes presupposed by another code of the same order, such as the prison system and legal system) — or vertically via epistrata (codes presupposed by another code of a different order, such as the legal system relying on language, biochemistry, and so on). An example of parastrata in Qwerty is using keys in a game for movement.

A keyboard lends itself as a paradigmatic example because it combines so many forms of code, at so many levels. There are linguistic codes (letters in English words), physical codes (limitations of human hands), and mechanical codes (technical specifications). Further, a keyboard embodies various semiotic distinctions, such as code vs. territory or form vs. substance. Qwerty takes the alphabet out of its ‘territory’, as ordered in the ABCs song; likewise, the fingers of the typist are deterritorialized onto the keyboard. In this sense, Qwerty is an abstract diagram of stratification.

While typical semiotics deals with signifiers and signifieds, Deleuze & Guattari draw from Hjelmslev’s quadripartition. In a verbal language, expression-substance is the continuum of sounds producible by the human vocal apparatus; expression-form is its differentiation into phonemes (signifiers); content-substance is sphere of concepts; and content-form is its differentiation into signifieds [via].

Analogously, if substance is the physical aspect, then a physical keyboard is content-substance, while Qwerty is an expression-substance. Likewise, the expression-form is the signifier being typed, while content-form is the signified. (Don’t quote me on this, I’m sure I mangled it.) The main point is that variations such as Azerty keyboards for Francophones can be localized onto one of these planes.

Therefore, more broadly, qwernomics is an analysis of stratification or capture, as Qwerty directs codes’ flows of intensities. Audaciously, we can say that qwerty is a cultural genome, with knowledge geologically deposited into it. By way of a quasi-diagrammatic analysis of the keyboard through stratograms, we can hack the cryptographic protocol that the qwerty apocalypse has delivered to us.

The Extreme Qwernomic Thesis

If all this sounds increasingly weird, then good. It gets weirder.

Above I stressed qwernomics’ skepticism towards global criteria for optimality, and we can radicalize this still further. One form has shown up in empirical studies: that even prior to Qwerty there was already a pool of typing competence that settled the arrangement of Qwerty. Hence, Qwerty has no localizable origin, and the entire geopolitical structure of world history is Qwerty-shaped.

Thus the ‘extreme qwernomic thesis’ can perhaps be most cogently stated as follows:

the highly obscure historical stratodynamic process from which we have inherited the keyboard is the same process that has provided us with all the cognitive resources that we could conceivably gain access [to] in investigating our object" [2016, VII, around 41:00]

We can restate this in various other ways. (I’m mostly just plagiarizing Land here.)

The core idea is that of an immanent cognitive horizon: if qwerty is the machine talking about itself, there is no meta-discourse on the machine that we’re ever going to find. There is no position of purchase or overview or superior perspective, because the function of overviewing is itself a product of a stratic mechanism, a symptom of stratic embeddedness. Hence there is no possible that isn’t already within the processing system. The overview position itself is structured inside that strata.

Qwerty is the revelation of a transcendental cognitive engine, in that the cognitive machinery we are trying to put into play has to come out of our object. Faced with the immanence of all criteria, there is no way out, but only through — mining parts of the keyboard for parts of our theory, in the form of “delirialized, wild particles of conception” such as the Ctrl key as zone of transference between dimensional systems, or Qabbalistic resonances of the Esc key. The purpose of these schizoid parts of qwernomics is to explore the extent to which qwerty is a transcendental cognitive resource.

Conclusion

Most of these statements sound absurd when applied to the keyboard, but the same considerations come into play for concrete problems where we don’t have nearly as much of a conceptual foothold.

The ultimate stakes of qwernomics are to delineate the meaning of a ‘critique’ of capitalism, in the Kantian sense of a global tribunal of reason. Many people will be sympathetic to the notion that there is no such universal position; yet, even by calling something a local optimum at all, we’re already implying the existence of some position of transcendent criticism. At a bare minimum, qwernomics makes us aware of the ‘spectre of the universal’ by which we criticize standards.

While I still haven’t digested all this, it seems that simulation offers an interesting counterpoint. Instead of looking at our path from some external position and saying it was wrong, simulations immanently generate a multiplicity of paths to which we can compare our own. We don’t need an Archimedean point, but only to differentiate the various strata as manifested in parameters that can undergo variations. Instead of a global perspective, we generate a garden of forking paths to populate the search space with purely local theories. This seems entirely compatible with the points made above. In a word, we can radicalize qwernomics still further into computational stratoanalysis.

References

- David, P. (1985). “Clio & the Economics of QWERTY.” American Economic Review 75(2), pp. 332-7

- Land, N. (2004, Dec 23). Intro to Qwernomics. Hyperstition blog.

- Land, N. (2016). Qwernomics: Path Dependency & Semiotic Fatality, Sessions I-VIII.

- Le, V. (2019). “One Two Many: On Nick Land’s Numbering Practices”. Colloquy 37, pp. 80–105

- Liebowitz, S. & Margolis, S. (1990). “The Fable of the Keys.” Journal of Law & Economics 33, pp. 1-25