One of my more recent code projects replicated a paper by Burg, Boyle & Lang (2000), which used constraint-solving to analyze the non-linear timeline in Faulkner’s story “A Rose for Emily”.

I like this paper because it’s quirky. Most digital humanities is confined to a handful of tools, such as statistically analyzing a corpus, or mapping characters’ social networks. Constraint-solving is a brand new tool, so the paper is evocative not only for its results, but also for the new possibilities it hints at.

First I’ll go over the code part, then what it means for the story, then some speculative conclusions.

Non-linear Chronology

Here I’m giving an informal overview of what the code does, which the reader can skim quickly to understand the results. For those more interested in the code, this repository is the place to look.

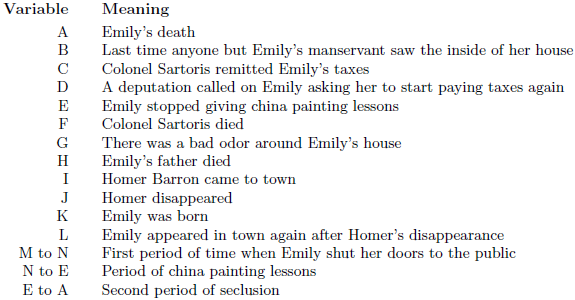

Here’s a table of the main events in the story. (It’s fine to just skim it for now.)

These events are given in the order they appear in the story, which clearly is highly nonlinear. However, Faulkner also includes various inter-temporal references. We can encode these as equations or inequalities — if A occurred 6 years before B, we get: A+6=B. All these references are listed in the table below. (I highly recommend skipping, but it will help later on.)

What the constraint solver does is to test possible years when each event could have occurred, which must satisfy the constraints, i.e. the series of intertemporal equations or inequalities. If the constraints are inconsistent, the program identifies the ‘minimal conflict set’, where removing any one will make the rest consistent (Burg, Boyle & Lang, 2000: 385). If the constraints can be satisfied, the program outputs the range of years in which each event could have consistently occurred.

If it helps, I think of constraint-solving by analogy with linear programming, a common tool in economics to allocate resources with different values (e.g. prices of goods being delivered, nutrients in a diet) subject to a budget constraint (travel costs, cost of each food item). The difference is that with constraint-solving we’re not trying to maximize anything, we just want consistency.

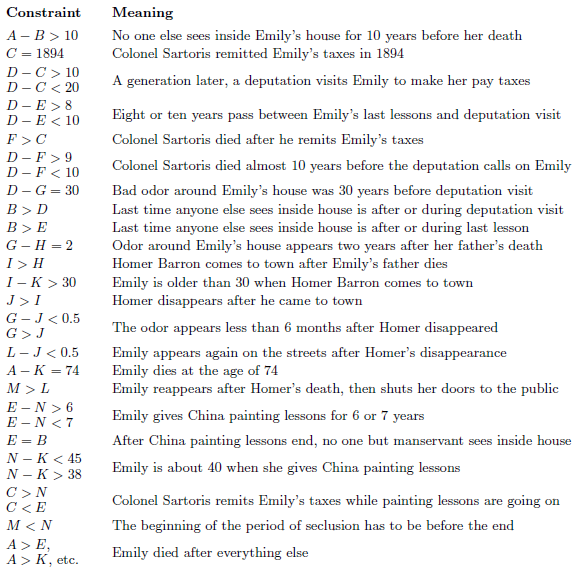

To illustrate the possible chronologies given by the program, I made a little diagram.

The top two lines are the order of events given in the story, versus a possible chronological ordering. The third line just rearranges the second line; it’s the order that would make all the red lines vertical. The bottom two lines illustrate possible orderings of events; there are 10 in all, but they’re quite repetitive. Among these, the only events whose order completely flips are E and F, hence the red X. The small blue brackets mean that these two events (could have) occurred in the same year.

Computational Hermeneutics

Now let’s see what this all means for how we interpret the story.

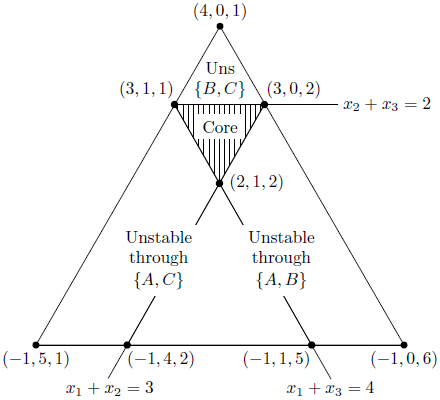

The first thing to jump out when we run the code is that the following statements are inconsistent:

| D - E >= 8 | Eight or ten years pass between Emily’s last lessons and deputation visit | |

| B >= D | Last time anyone else sees inside house is after or during deputation visit | |

| E = B | After China painting lessons end, no one but manservant sees inside house |

The first constraint comes from the sentence: “A deputation...knocked at the door [D] through which no visitor had passed since she ceased giving china-painting lessons [E] eight or ten years earlier” (1930: §1). The latter gives D - E >= 8.

However, later the story notes: “The front door closed upon the last [painting pupil] and remained closed for good” (1930: §4), with ‘for good’ implying E = B.

There are several ways to reconcile these claims. One is that the deputation entered (or pupils exited) a door other than the front door. Another possibility is that there was an unspecified visit to the house following the deputation visit, and this person was the last to see inside the house.

The original authors opt to remove the constraint E = B from the program, since this is the least specific temporal reference of the three, and may even have been an error on Faulkner’s part. This adjustment causes the program to work.

Recalling the diagram above, the main variations among the different chronologies are whether the tax remission (C) occurs at the beginning of Emily’s china-painting lessons (C = N), in the middle (N < C < E), or at the end (C = E); whether Colonel Sartoris dies while Emily is still giving lessons (F <= E) or after (E <= F); and whether the deputation are the last people to see inside Emily’s house (B = D), or whether someone else is (B <= D).

More interestingly, it turns out that there’s a big debate in Faulkner scholarship about whether the year Emily’s taxes were remitted (C) is the same as the year of her father’s death (C = H), or whether the tax remission occurs at the time of the china-painting lessons (N =< C =< E). Burg, Boyle & Lang’s (2000) program unequivocally supports the latter interpretation.

Lastly, in an early draft of the story, Faulkner included the sentence “that day in 1904 when Colonel Sartoris...remitted her taxes dating from the death of her father 16 years back, on into perpetuity” (in Burg, Boyle & Lang, 2000: 387). The authors set C = 1904 in their program, but find it inconsistent. However, leaving C = 1894, they find that Emily’s father could have died 16 years before, i.e. H = 1878 is consistent.

The Simplex of Meaning

In the rest of their paper, the authors try to narrow down the timeline to a single interpretation. The other time constraints imply that Emily must have been born between 1842 and 1856 (1842 <= K <= 1856), and the authors surmise that Faulkner set the story during 1924, the year he wrote it (2000: 385). This gives a birth date of K = 1850, from which they infer various other dates.

Curiously, this fails to replicate in my version of the code. The main difference between my program and theirs is that mine uses integers (for years) and theirs uses real numbers. Yet, this in itself doesn’t explain the failure. I still haven’t managed to pin down the exact reason. Here’s a nice place to tinker with the code, if the reader is so inclined.

More crucially, I think the idea of using a computer program to find the unique meaning of a text is an impoverished view of what the program actually does. Rather, the truly novel element of Burg, Boyle & Lang’s approach is that they can model the space of contested meanings within a text.

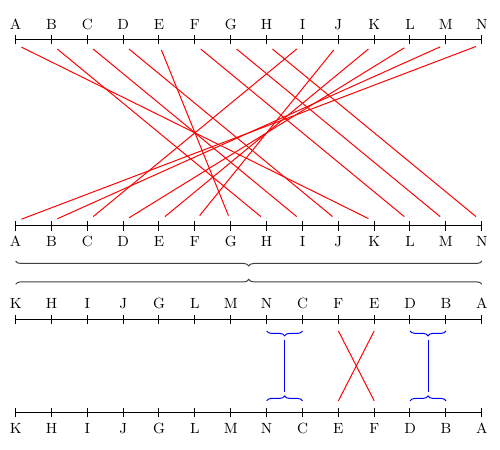

In the mathematical theory of linear programming, such a space is called a simplex. With only two variables, say Emily’s death (A) and birth (K), we know that she died at age 74 (Faulker, 1930: §4), so that A = K+74. Thus, our ‘simplex’ here is just a line, where the farther back K is, the farther back A is in turn. Further, suppose three variables (x, y, z) must add up to 3, and are greater than zero. Then the different combinations (including decimals) take the form of a triangle, whose vertices are (3,0,0), (0,3,0), and (0,0,3).

With large numbers of constraints, the simplex is an n-dimensional surface far beyond human visualization. In a very real sense, this monstrous geometrical object is the space of possible meaning for Faulkner’s chronology.

While impossible to represent pictorially, one can imagine a series of dials, one for each constraint. Adjusting the date of one (e.g. Emily’s death A) forces all the other dials to adjust in turn. The key to look for would then be discontinuities: in adjusting one constraint, all the other constraints move incrementally, but then one or more suddenly ‘jump’ to a far-away value. Such discontinuities in the space of meaning may likely be what gives rise to conflicting interpretations.

Conclusion

“A Rose for Emily” is one of Faulkner’s most widely read stories, and it’s difficult to imagine how new insights might still be gleaned about it. Thus it’s a pleasant surprise that simply listing unambiguous temporal references in a computer program can clarify long-standing debates on the storyline.

Burg, Boyle & Lang (2000: 388) suggest their method may also be applied to The Sound and the Fury, or any story with a non-linear chronology, given enough inter-temporal constraints. Thinking geometrically, it would be fascinating to see if Faulkner’s simplexes have a ‘shape’ distinct from those of other authors.

Another possibility is encoding multidimensional mathematical objects (e.g. a Klein bottle) as temporal constraints, then writing a story that satisfies them. Still further, one can imagine a detective story in which a temporal inconsistency is the key to solving the case.

In sum, digital humanities should be a tool for expanding the meaning of a text, rather than identifying a single ‘correct’ meaning. By identifying different and equally valid interpretations of the timeline for “A Rose for Emily”, a digital approach to the text can thereby help foster debate rather than stifle it.